On the Removal of 'Homosexuality' from the DSM

An Origin Story that Reveals A Fundamental Philosophical Issue about Mental Disorders

In April it will be the 51st anniversary of the removal of homosexuality as a category of psychiatric disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The DSM is often referred to as “the Bible of Psychiatry” due to its influence on the profession and its size in print. The removal of homosexuality from the DSM raises has generated lots of debate about whether psychiatric disorders are based in scientific discovery or are labels invented for social/political control. Here we will take a brief look at the history of the inclusion and the removal of ‘homosexuality’ from the DSM to shed some light on the core ethical and conceptual issues at the heart of psychiatric classification, definition and diagnosis.

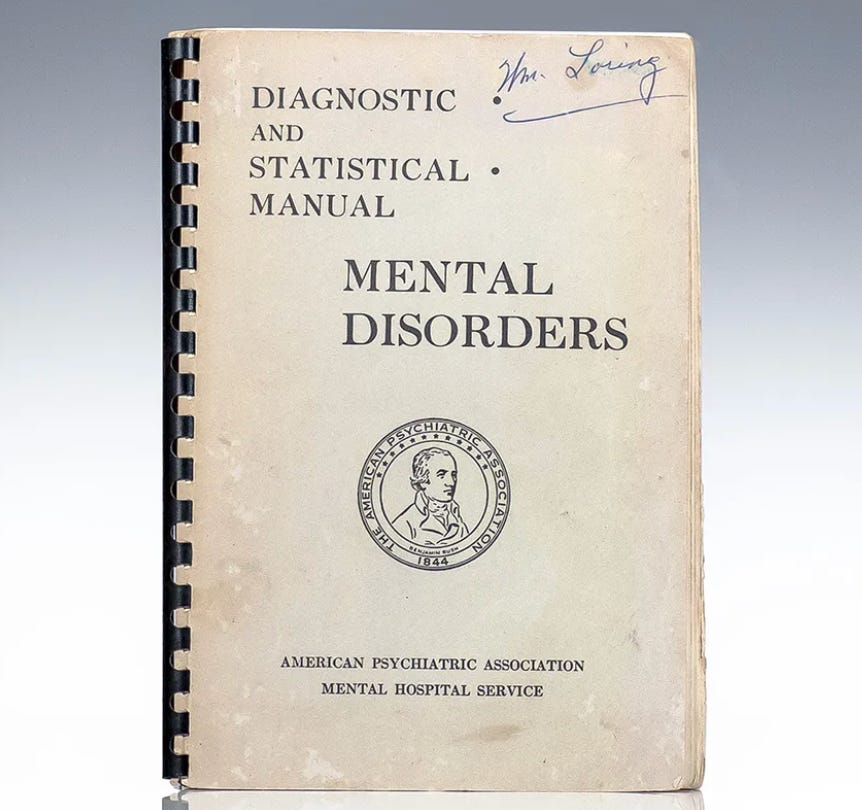

The first edition of the DSM (DSM-1) was published in 1952. It was only 32 pages long and contained a list of 106 disorders. (Horwitz 2011) Homosexuality as included and listed as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” The DSM-I and its sequel were steeped in the dominant psychoanalytic language of the times.

The DSM-II was over three times the original edition, but was still only 109 pages (compared with the Biblically sized DSM-5, which is 947 pages).

The DSM-II listed homosexuality as the first and prime example of “sexual deviations,” and defined “the psychopathology” as follows:

This category is for individuals whose sexual interests are directed primarily towards objects other than people of the opposite sex, toward sexual acts not usually associated with coitus, or toward coitus performed under bizzare circumstances. Even though many find their practices distasteful, they remain unable to substitute normal sexual behavior for them.

Dr. Charles Socarides was a leading defender of the view that homosexuality was a psychopathology. He was a prominent member of the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research. He rejected the religious view that homosexuality was a choice, a crime or an immoral act. Rather, he argued that it was a form of neurosis that originated from “smothering mothers and abdicating fathers” and should be treated as a form of neurotic conflict. From the 1950s-1990s he attempted to “cure” gay men with psychoanalysis, but there is no evidence that anyone was ever “cured” from his conversations with them. (Lieberman and Ogas, 121-122)

In the early 1970s there were mounting arguments from courageous gay activists, sympathetic psychiatrists and APA officers that homosexuality should no longer be considered a mental disorder. Dr. Robert Spitzer was a major agent in the removal of homosexuality from the DSM. In 1968 he took on a leadership role in examining the status of homosexuality in psychiatry, and allegedly did not have a strong stance on the issue when he began examining the issue. There were three main events that led him to the view that being gay was not a mental disorder. (Wakefield 2024)

First, there was the historic presentation at the APA meeting in 1972 by Dr. H. Anonymous. He was later revealed to be the psychiatrist Dr. John Fryer who wore a costume and spoke through a microphone that distorted his voice. His talk began with the words, “I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist.” Fryer went on to descrive the oppression of gay psychiatrists who had to hide thier sexual orientation from their colleages and keeping their jobs secret from other gay people who hated psychiatry. (Lieberman and Ogas, 123-125)

Second, after hearing the protests of gay activists at the 1972 APA meeting and other events that year, Spitzer organized a debate on the topic. At that debate, he was moved by Dr. Charles Silverstein’s arguments that treating homosexuality as a mental disorder was harming gay people by justifying coersive laws. He contended that there was no evidence of psychological problems among gay people, and argued that treating homosexuality as a mental disorder was just “society’s moral judgment dressed up as medicine.” (Wakefield 2024)

Third, at the 1973 APA meeting, the influential gay activist Ronald Gold gave a paper titled, “Stop it, You’re Making Me Sick!” and took Spitzer to a secret meeting of the “Gay-PA”, which was a meeting of closeted gay psychiatrists. Spitzer was surprised to see many prominant and “high-functioning” colleages at this meeting.

As a result, later in 1973, Spitzer drafted a policy statement declaring that the APA should support civil rights for gay people. Additionally, he drafted arguments for the removal of ‘homosexuality’ from the DSM and circulated them to all APA members for consideration. As Jerry Wakefield reports

Spitzer argued that what is important is the ability to have satisfying intimate sexual and emotional relations with another person, but that whether the person is of the same or a different sex is not important. Thus, homosexual individuals are not impaired. However, if distressed, they could qualify as disordered. (2024, 285)

The argument was compelling and it led to the removal of ‘homosexuality’ from the DSM.

More on Spitzer’s revolution in Psychiatry with the DSM-III and its pros and cons in later posts. Since the publication of the DSM-III, ‘homosexuality’ has not been included in the DSMs. However, there remain traces of it in the categories of “Paraphilic Disorders” that occur in DSM-III and all later edition. Another subject for future posts.

How should we understand the revisions that have occurred in the DSM? Some suggest that episodes like this reveal that the DSM revision process is fundamentally political, which shows that mental disorders are not genuine pathologies—they are labels that society uses for the purposes of classifying people as ‘mentally ill’ and thereby removing their rights. Let’s call this view “the labeling theory.” Others contend that the DSM does a reasonable job at identifying genuine mental illnesses, and that the revision process is just a part of the scientific enterprise of understanding these difficult disorders of the brain, mind and behavior. Let’s call this view “the standard medical view.”

I’ll say more about the origins and rationale for these theories in future posts. Stay tuned for more on the history and philosophy of psychiatry!

Acknowledgements

I recently discussed Wakefield’s article with a lively group of ECU Psychiatry residents. I’m grateful to them for the lively discussion. Only a small fraction of what I learned from that conversation is conveyed here.

References

Horwitz, Alan. 2021. “DSM: A History of Psychiatry’s Bible". https://www.press.jhu.edu/newsroom/dsm-history-psychiatrys-bible

Lieberman, Jeffrey and Ogi Ogas. 2015. Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Wakefield, Jerome. 2024. “R. Spitzer and the Depathologization of Homosexuality: Some Considerations on the 50th Anniversary.” World Psychiatry. 23(2): 285-286.

Great article! The ongoing evolution of psychiatric classification raises fundamental questions about the nature of mental disorders and the criteria used to define them. The tension between the 'labeling theory' and the 'standard medical view' remains particularly relevant as new revisions continue to reshape the landscape of mental health.

How do we ensure that diagnostic categories remain clinically meaningful while avoiding the risk of pathologizing variations in human experience?

Thanks. One idea behind much of psychiatry, which is little spoken about, is that someone asks for help. This is not usually because they have read the science, it is usually because they (or someone close them) are reporting significant loss of functioning, or stress to self or others. The dsm then attempts to identify a way to classify what might be behind this to guide treatment. The science of deciding what is abnormal is then half of this process and measuring loss of functioning or stress (non research based) is the other. What becomes political is perhaps what society finds “stressful”. And in what places has a psychiatric concept developed to help society with its more prejudiced ‘stresses’.