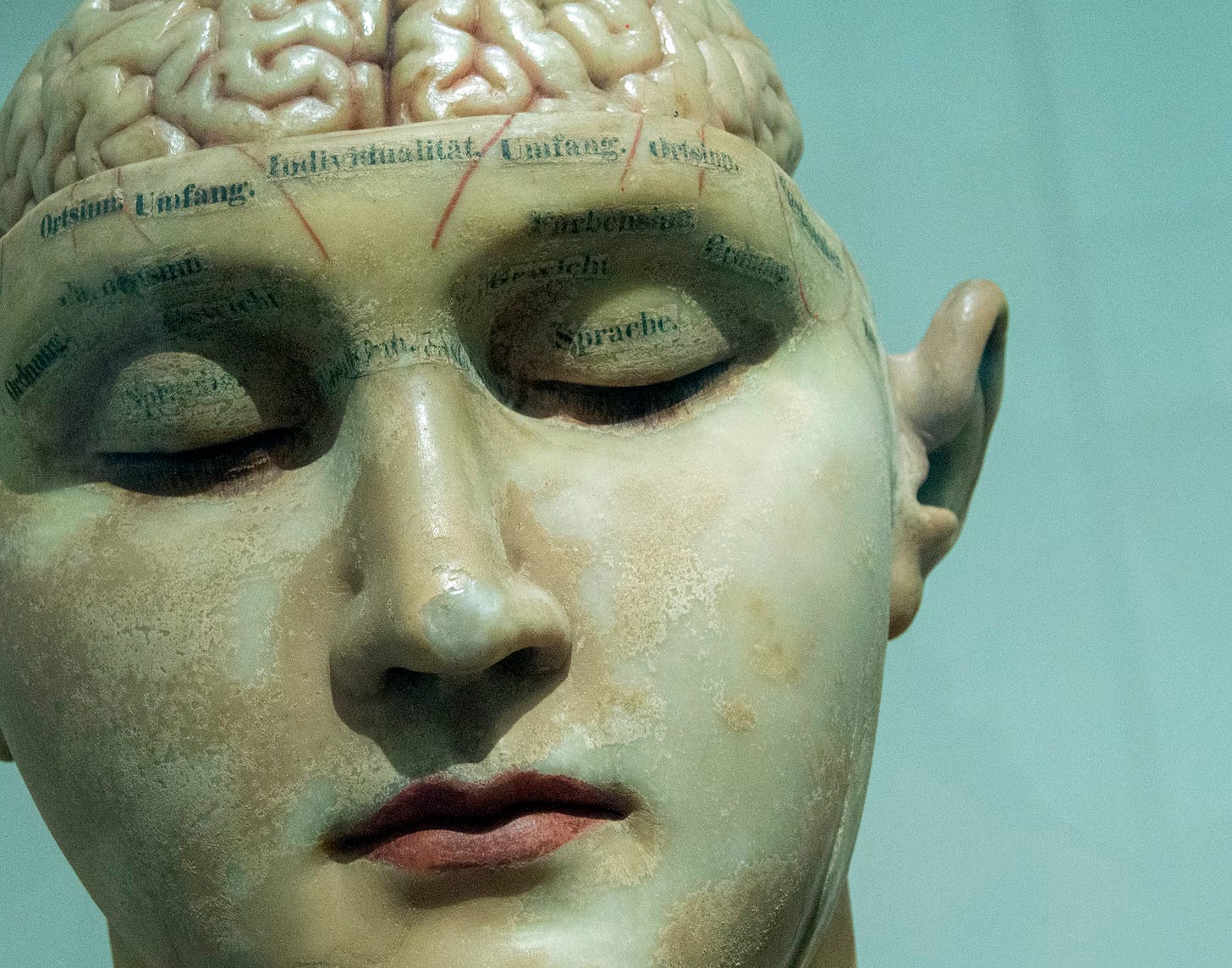

Introduction: Why Defining ‘Mental Disorders’ Matters

What makes a condition a mental disorder? Does it require distress, impairment, or something more complex? This question is not just a matter of academic debate. It has significant implications for clinicians who need a concept of mental disorders to distinguish pathological from non-pathological conditions. The distinction matters for deciding whether an insurance company will cover the treatment of a condition. History is also filled with diagnoses that reflect cultural biases rather than scientific facts: drapetomania, the so-called “mental disorder” of slaves seeking freedom; the classification of homosexuality as a psychiatric illness. This post examines Jerome Wakefield’s influential harmful dysfunction account of mental disorders, considers its strengths and limitations, and sets the stage for future posts and discussions about the nature of mental disorders.

Revisiting Spitzer on Depathologizing Homosexuality

When Robert Spitzer argued that homosexuality should not be considered a mental disorder, and the category should be removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-III), his argument to the American Psychiatric Association was based on statements about general features of mental disorders. He argued that if a mental condition is pathological, then that condition must either regularly cause subjective distress or it must be regularly associated with a generalized impairment in social effectiveness or functioning. (Discussed in Wakefield 2024 and in my previous post.) Spitzer argued that sexual attraction to, and sex with, persons of the same sex often does not cause subjective distress and are not regularly associated with impairments in social effectiveness or functioning, homosexuality is not a mental disorder. So, Spitzer’s understanding of the general features of the concept of mental disorder were used to argue that this particular “mental condition” should not be considered to be a mental disorder. Since major depressive disorder does involve subjective distress and impairments in social functioning, it does satisfy the general criteria, and may count as a mental disorder.

The DSM-III and all later editions of the DSM contain a general definition of mental disorders. We’ll look at the DSM-5 definition and some problems with its application to specific disorders in a later post. (For a very good discussion of the issue in the DSM-5, see Singh and Sinnot-Armstrong 2015.)

Spitzer’s argument illustrates how our understanding of mental disorders hinges on general criteria like distress and impairment. But what makes a condition a genuine disorder? Jerome Wakefield’s ‘harmful dysfunction’ account provides a compelling framework that bridges the gap between biological facts and social values: two frameworks often seen as competing rather than complementary.

A Brief Overview of the Harmful Dysfunction Account

Professor Jerome Wakefield

The classic paper where Wakefield defends this view is “The Concept of Mental Disorder: On the Boundary Between Biological Facts and Social Values” (1992) and he has consistently defended his stance throughout his distinguished career.

The question of whether mental disorders are based in biological facts or social norms is one of the first that gripped my attention when considering the people that I knew who had a psychiatric diagnosis. I wondered whether they were just labeled that way because they did not conform with social norms or whether they had a “chemical imbalance” in the brain, a genetic disorder or some other type of brain disorder.

Wakefield argues that a disorder is a harmful dysfunction. On this view, disorders have an evaluative/normative component and a factual component: the harm and the dysfunction. In a compressed summary of the view, Wakefield writes,

“a disorder exists when a failure of a person’s internal mechanisms to perform their functions as designed by nature impinges harmfully on the person’s well-being as defined by social values and meanings.” (373)

This account of disorder is intended to apply to both physical/somatic and mental disorders. (374) However, the emphasis is on mental disorders since their nature and existence is more controversial. Wakefield also uses the term ‘disorder’ in a technical way:

“Also, some writers draw distinctions among disorder, disease and illness. Disorder is perhaps the broader term because it covers traumatic injuries as well as disease/illnesses.”(374)

Wakefield defines dysfunction as the failure of an internal mechanism, such as cognitive or emotional processes, to function as nature intended. For example, if someone has a phobia of rabbits, their fear response is malfunctioning because rabbits pose no real threat.

When Wakefield says that our bodily functions are “designed by nature” he is not endorsing an “intelligent design” theory of the creation of the universe and divine providence. Rather, he explicitly endorses evolutionary biology as the best explanation for the design of our natural functions/mechanisms. (383)

The harm component refers to the dysfunction’s negative impact on a person’s well-being, as defined by cultural norms and social values. Consider a person with severe anxiety who cannot leave their home. Their heightened fear response, likely rooted in evolutionary mechanisms designed to protect us from danger, becomes dysfunctional when it misfires in everyday situations. The condition becomes a disorder because it causes significant harm, impairing the person's ability to work, maintain relationships, and enjoy life—harms that are recognized as detrimental within their cultural context. Wakefield argues that having a dysfunction is not sufficient to be considered a disorder. He contends,

“To be considered a disorder, the dysfunction must also cause significant harm to the person under present environmental circumstances and according to present cultural standards. For example, a dysfunction of one kidney often has no effect on the overall well-being of a person and so is not considered to be a disorder; physicians will remove a kidney from a live donor for transplant purposes with no sense that they are causing a disorder, even though people are certainly naturally designed to have two kidneys.” (383-384)

The harms relevant to having a disorder, on this account, are not just abstract claims about diminished well-being or bare harms done to a person: the relevant harms must be mediated by cultural norms.

To illustrate the harmful dysfunction account, consider a person with severe anxiety who cannot leave their home. Their heightened fear response, likely rooted in evolutionary mechanisms designed to protect us from danger, becomes dysfunctional when it misfires in response to almost everything outside of the person’s home. The condition is a disorder because the dysfunction causes significant harms that are recognized as detrimental within the person’s culture: the disorder impairs the person's ability to work, maintain relationships, and enjoy life.

This quick summary of Wakefield’s view does not give it justice, and I have not discussed its merits relative to other theories. The 1992 paper discusses how the harmful dysfunction view is an improvement over the skeptical anti-psychiatry view, the value approach to mental disorders, disorders as whatever professionals treat, two scientific theories of disorder (statistical deviance and biological disadvantage), and the DSM-III general definition of ‘mental disorder’. I agree that the harmful dysfunction view is an improvement over those views. However, there are serious criticisms of Wakefield’s theory that are worth considering.

Criticisms and Limitations of the Harmful Dysfunction Account

There is a vast literature responding to Wakefield’s view. I’m not going to cite the relevant literature here, and will just briefly describe the main concerns.

Concern with the general account of disorder: Wakefield’s broad definition of disorder, which includes both injuries and diseases, seems to conflict with common usage. For instance, most people would not describe a broken toe as a disorder. They would call it an injury. Also, does the harmful dysfunction account entail that disorders are bad for the person who has them? There is growing support for the view that disorders are “mere differences” from normality and are not necessarily bad for the people who have them.

Concern with the evolutionary explanation of dysfunction: By relying on evolutionary biology to define dysfunction, Wakefield’s account assumes that natural selection has designed our internal mechanisms for specific purposes. However, what if nature designed people to deteriorate in pain and die in order to make room for the younger members of the species to reproduce. Also, some argue that evolutionary explanations of the natural design of our physiological mechanisms are often unfalsifiable.

Concern with the culturally relative account of harm: Wakefield’s account defines harm using social values and meanings, which can vary across cultures. However, if harms are determined by social norms, then his account is open to the criticism that psychiatry is just an institution for the enforcement of local social norms. This raises concerns that certain behaviors might be classified as disorders in one society but considered normal in another, leading to potential misdiagnoses and stigma.

Competing Theories of Mental Disorders

In future posts, we will examine competing theories of mental disorder that challenge Wakefield’s reliance on evolutionary biology, his culturally relative definition of harm and the claim that internal dysfunction is necessary for mental disorders.

Gert, Culver, and Clouser’s Objective List Theory of Mental Maladies

Bernard Gert, K. Danner Clouser, and Charles Culver propose an alternative framework that avoids both evolutionary assumptions and culturally relative definitions of harm. (Gert, Clauser and Culver, 2006) Instead of defining disorders as internal dysfunctions that cause harm according to social values, they define maladies as conditions that prevent individuals from achieving basic goods that are universally valued, such as freedom from pain, the ability to function independently, and the capacity to experience pleasure.

Unlike Wakefield’s account, which requires both dysfunction and culturally defined harm, Gert, Culver, and Clouser argue that the presence of objective harm alone is sufficient to classify a condition as a disorder. In a future post, we will examine the strengths and limitations of this objective list theory, including whether its universal criteria can account for the diversity of human experiences and cultural contexts.

Labeling Theory, the Social Construction of Disorder, and Thomas Szasz

Labeling theory, associated with sociologists like Edwin Lemert and Thomas Scheff, takes a radically different approach by rejecting the idea that mental disorders are objective conditions. Instead, this theory argues that mental disorders are social constructs: labels applied to behaviors that deviate from societal norms. Thomas Szasz, a leading figure in this tradition, famously argued that “mental illness” is a myth, claiming that psychiatric diagnoses often serve as tools of social control rather than scientifically grounded medical categories.

In a future post, we’ll examine the implications of labeling theory for psychiatry and mental health care, including its challenges to diagnostic practices, its critique of stigma and discrimination, and its enduring influence on contemporary debates about neurodiversity and the medicalization of everyday life.

At the heart of these competing theories lies a challenging philosophical question: Are mental disorders objective phenomena that scientists discover or are they conceptual categories that societies invent?

Wakefield’s harmful dysfunction account straddles this divide, grounding dysfunction in biology while acknowledging that the concept of harm is shaped by culture.

Looking Ahead

In the next few weeks, we will examine Gert, Culver, and Clouser’s objective list theory in more detail. We will compare it with Wakefield’s harmful dysfunction account and evaluate whether a universal definition of disorder really is useful for the theory and practice of mental health. We will also look at the work of the labeling theorist, libertarian and psychiatrists, Dr. Thomas Szasz,

What do you think are the pros and cons of Wakefield’s harmful dysfunction account? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

References

Gert, Bernard, Charles Culver and K. Danner Clouser. 2006. Bioethics: A Systematic Approach. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press.

Singh, Devin and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong. 2015. “The DSM-5 Definition of Mental Disorder.” Public Affairs Quarterly. 29 (1): 5-31.

Wakefield, Jerome. 1992. “The Concept of Mental Disorder: On the Boundary Between Biological Facts and Social Values.” American Psychologist. 47(3): 373-388.

Wakefield, Jerome. 2024. “R. Spitzer and the Depathologization of Homosexuality: Some Considerations on the 50th Anniversary.” World Psychiatry. 23(2):285-286.

Interesting but I wanna hear how it's received by a *full* spectrum of people who truly suffer from the problems - if not all voices and experiences are fully and equally included in the convo it's just privileged people going back and forth about the "other". That is an additional power dynamic that must be factored in - without exclusion of - other power dynamics.

A useful starting point for me is to consider that there is no cell, organ or system that works perfectly in everyone all the time. While we could perhaps try to unpack what "works" and "perfectly" might mean in this context, I think most people from across the nature-nurture spectrum would nevertheless find the above assertion broadly acceptable.

If you then further accept that human expression is entirely dependent on biology (i.e. that there is no independent non-physical element), then the idea that the most complex system we know of - the brain - has never deviated from perfect functioning in any aspect in anyone anywhere and never will, is much harder to accept. The debate therefore is about how to detect and define these "malfunctions", not about whether they might exist at all.